Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians are a historical national minority in the region of Dalmatia which is now predominately part of Croatia.

When Austria occupied Republic of Venice's region of Dalmatia in 1815 the Venetian (Italian) population made up, (according to the Italian linguist Bartoli) nearly one third of Dalmatia in the first half of the 19th century. The 1816 Austro-Hungarian census registered 66 000 Italian speaking people among the 301 000 inhabitants of the Kingdom of Dalmatia, or 22% of the total Dalmatian population. After World War II, the Dalmatian Italian population was reduced to 300 in todays Croatia - Dalmatia and 500 in Montenegro. [1][2][3]

Today they reside mostly in the city areas of Zadar, Split, Trogir, and Sibenik in Croatia, and Kotor, Perast, and Budva in Montenegro. In other parts of Croatia, there are Italian communities located in the Istrian peninsula and the city of Rijeka.

Note: During the Austro-Hungarian census of 1910,[4] 2.8% Italians were registered in the Kingdom of Dalmatia. This high drop can be explained by immigration as well as families who where of dual culture (Italian-Croatian), decided to register themselves as Croatian.

Early History

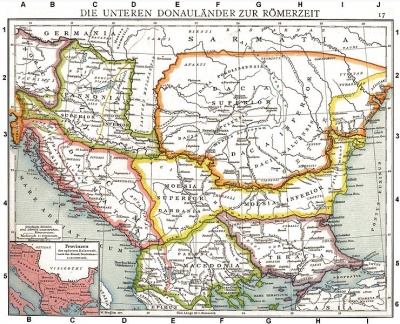

Roman Dalmatia

According to scholar Theodor Mommsen, Roman Dalmatia was fully Latinized by 476 AD when the Roman Empire disappeared. More recent theories have suggested that this would only apply to cities and towns, whilst in the country side, this would not have been the case.

During the Barbarian invasions of the 6th to 9th century, [5] certain Slavic tribes allied with Eurasian Avars [6][7] invaded and plundered Byzantine-Roman Dalmatia. This eventually led to the settlement of different Slavic tribes in the Balkans. Modern scholarly research now puts the time of the main settlement of the Slavic tribes in the region to be much later.[8] Archaeological evidence found in the old Roman city of Salon and in particular the artefacts found at the Old Croatian grave sites in Dalmatia (during recent excavations) [9] seems to confirm this. Some historians have placed the arrival of main groups of Slavs and their settlement more in the region of the late 8th and early 9th century. The early sources must have reflected the raid activity of the Slavic tribes within Roman Dalmatia and maybe some very small scale settlement.

The Roman population survived within the coastal cities,[10] in the inhospitable Dinaric Alps (these people were later known as "Morlachs" or Vlachs) and for a while on the islands. Many of the Dalmatian cities retained their Romanic culture and Latin language. Among these were Jadera (Zara/Zadar), Spalatum (Spalato/Split), Ragusa (Dubrovnik) and Trau (Trogir). These areas developed their own Vulgar Latin the Dalmatian language,[11] a now extinct Romance language.[12] Many coastal cities and towns or the region (politically part of the Byzantine Empire) [13] maintained political, cultural and economic links with the Italian peninsula through the Adriatic sea. Communications with the mainland were difficult because of the Dinaric Alps. Due to the sharp orography of Dalmatia communications between the different Dalmatian cities occurred mainly through sea links. This helped Dalmatian cities to develop a unique Romance culture, despite the mostly Slavicized mainland. Political rule over the province often changed hands between the Republic of Venice and other regional powers, namely the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire), Carolingian Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia, and the Kingdom of Hungary.

Late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance

From the late Middle Ages onwards certain sections of the population slowly started to merge with the Slavic peoples of Dalmatia. This process was most evident in the coastal and island regions of Dalmatia and in the Republic of Ragusa. The 1667 Dubrovnik earthquake, which destroyed the greater part of Dubrovnik (Ragusa) has been cited as a turning point for the make up of the ethnic population of the Republic. This new Slavic population within the Republic became, with time, Romanised (adopted Latin culture). Within Ragusa's community there were mixed marriages (i.e. Roger Joseph Boscovich).[14]

Croatians in Dalmatia, as well as other regions, have language remnants of the extinct Romance Latin language - Dalmatian and additionally there are influences of old Venetian in the local dialects. The Republic of Venice controlled most of Dalmatia from 1420 to 1797. During that period, part of its Slavic population were Romanised.

"Venetian Dalmatia", as it was called by the Venitians, enjoyed periods of economic prosperity with the development of arts and culture. Dalmatia was greatly influenced by the northern Italian Renaissance and many buildings, churches and cathedrals were constructed in those years, from Zadar and Split to Sibenik (Sebenico) and Dubrovnik.

Zara (Modern: Zadar) was the capital of Venetian Dalmatia. During these centuries, the Venetian language became the "lingua franca" of all Dalmatia, assimilating the Dalmatian language of the Romanised Illyrians and influencing partially the coastal Croatian language (Chakavian).

It is also important to mention migrations from the east, as the Ottoman Empire advanced into Europe. This greatly changed the ethnic mix in the region. Wars with the Ottoman's and other conflicts were all part of Venetian Dalmatia's history as well as internal strife within the province (i.e.Hvar Rebellion). [15][16] Looking back through its past, Dalmatia presents it self as a region of Europe with a very multicultural and multiethnic history.[17]

The Cultural and Historical Venetian Presence in Dalmatia

The original Roman Dalmatia is now divided between Croatia, Herzegovina and Montenegro. The cultural influence from the Republic of Venice is clearly evident in the urbanisation plans of the main Dalmatian cities of Croatia. One of the best examples is the one of Split (Spalato).

In 1880 Antonio Bajamonti (the last Dalmatian Italian Mayor of Split under Austrian rule) developed an urbanisation project of this city centred on the "Riva", a seaside walkway full of palms based on the Italian Riviera models. Today the Riva (with cafe bars) is used by the locals to walk in a typical Italian way from the "Palace of Diocletian" towards an old square called locally "Pjaca" (or square in Venetian).

In Dalmatia, religious and public architecture flourished with influences of the northern Italian Renaissance. Important to mention are the Cathedral of St James in Sibenik, the Chapel of Blessed John in Trogir, and Sorgo’s villa in Dubrovnik.

Musical styles

In some of the musical styles of Croatia it is quite evident that there was a merging of Slavic and Italian music. One such musical style that demonstrates this is Klapa music (klapa is an a cappella form of music - Venetian: clapa "singing crowd"). Klapa singing dates back centuries. The arrival of the Slavs to Dalmatia and their subsequent settlement in the area, began the long process of the cultural mixing of Slavic culture with that of the traditions of the Roman-Latin population of Dalmatia.

The Klape appeared in the coastal and island regions of Dalmatia. In the 19th century a standard form of Klapa singing emerged. The traditional Klapa was composed of up to a dozen male singers (in recent times there are also female Klape groups). Church music heavily influences the arrangements of this music giving it the musical form that exists today.

Perast in Coastal Montenegro

An example of the Venetian cultural and historical presence can be seen in the small town of Perast (Perasto) in coastal Montenegro. Perast under the Republic of Venice (Albania Veneta), had four active shipyards and a fleet of around one hundred ships. Some of the buildings are ornate baroque palaces which resemble Venetian architecture.

The sailors of Perast were involved in the last battle of the Venetian navy, fought in Venice in 1797. After the fall of the Republic of Venetian (12/5/1797), Perast was the last city of the Republic to lower the Venetian flag. On 22 August 1797 the Count Giuseppe Viscovich, Captain of Perast, lowered the Venetian war-flag of the Lion of Saint Mark pronouncing the farewell words in front of the crying people of the city and then buried the "Gonfalon of Venice" under the altar of the main church within town of Perast.[18][19]

The population decreased to 430 in 1910. According to the "Comunita' nazionale italiana del Montenegro", in Perast there are people who's local dialect have remnants of the original Venetian dialect of Perast called "Veneto da mar".

Perspectives on Dalmatia

- In the 19th century the cultural influence from the Italian region originated the creation in Zadar of the first Dalmatian newspaper, edited in Italian and Croat: Il Regio Dalmata - Kraglski Dalmatin. It was founded and published by the Italian Bartolomeo Benincasa in 1806.

- After World War Two the Slavicisation of the of Dalmatia region was a government policy under the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. All cities, towns, villages, family and peoples surnames that are not of Slavic origin were being translated.[20] The policy was firstly implemented on a large scale with the creation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1918.[21]

- Dalmatia was named by the Romans after the Dalmatae (or Delmatae) Illyrian tribes [22] who inhabited the region.

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1797 – 1875) was an English traveller, writer and pioneer Egyptologist of the 19th century. He is often referred to as "the Father of British Egyptology". He was in Dubrovnik (then called Ragusa) in 1848, he wrote in his; Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a Journey to Mostar in Herzegovina:

Andrew Archibald Paton

Andrew Archibald Paton (1811 - 1874) was a British diplomat and writer from the 19 century. In 1861 he wrote in his; Researches on the Danube and the Adriatic: Or, Contributions to the Modern:

Maude Holbach (a 1910 travel guide)

- Dalmatia-The Land Where East Meets West by Maude Holbach (a 1910 travel guide from COSIMO books and publications New York USA):

The National Party

- The National Party (Narodnjaci) from the Kingdom of Dalmatia (Austro-Hungarian Empire). From the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century.

Luciano Monzali

Edwin Dino Veggian

Antonio Bajamonti

Antonio (Ante) Bajamonti, the most prominent Dalmatian Italian in history, once remarked:

Zadar during and after World War II

The chapter below is taken from the Secret Dalmatia Blog site, it is written by Alan Mandic.

More on Yugoslavia's Once Hidden History in Relation to Dalmatia

Displaced persons from the former Yugoslavia from 1940s and 1950s

The University of Western Australia study about Displaced Persons from former Yugoslavia right after World War Two, quote:

- Quote from the European Public Hearing on “Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes":

The former Communist Yugoslavia (which Croatia was part of) played a major role during the Cold War era in depicting this style of historical documentation (i.e Dalmatia - History, Culture, Art Heritage & the above mentioned "Mystifying the crimes of the occupiers, Titoism covered its own crimes.") of the region’s past. Yugoslav Communist history is now dogma in Croatia. This also would apply to the history of the Dalmatian Italians. Many of today’s Croatians live with this dogma as their reality even though the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. This dogma, falsehood was created by a totalitarian society. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia had a profound effect on the region.[36] So much so that it has created today’s political and cultural scene.

- Statement made by the contemporary historian Dr Danijel Dzino (Australian Research Council Australian Postdoctoral Fellow BA (Hons), MA, PhD Adelaide):

- Statements made by the contemporary historian John Van Antwerp Fine (Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Michigan):

Note: Communist Yugoslavia executed Historian - Kerubin Segvic. He was executed mainly for proposing a different historic model of how Croats came to the western Balkans in the middle ages than that of the Yugoslav government's state policies. [40]

Antun Travirka - Dalmatia (History, Culture, Art Heritage)

The region of the Western Balkans (former Communist Yugoslavia) has problems when interpreting its multicultural, multiethnic history and societies. This most certainly applies to the history of Dalmatian Italians, the former Republic of Ragusa and other regions.

This statement below comes from a book called Dalmatia (History, Culture, Art Heritage) written by Antun Travirka: "By the 14th century the city had become wholly Croatian'"' [41]

The book itself is primarily for the Croatian tourist market and is easily available in several languages in all major bookstores within Croatia.[42] This quote is on page 137 and it’s referring to the Republic of Ragusa. The old Republic of Ragusa (with it's famous city Dubrovnik) [43] is now within the borders of the modern Croatia. [44] This monolithic description is an outright lie and it’s a form of cultural genocide (the crucial word is wholly). Additionally the book did not even use the term Republic of Ragusa (the closest that it got to this was RESPUBLICA RAGUSINA on page 141)[45]. Ragusa the city's original name was used for more than a millennium. The statement is biased ultra-nationalistic propaganda and is not based on fact.

- Statement made by the contemporary historian John Van Antwerp Fine (Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Michigan, USA):

The City State and then latter the Republic was set up by Roman Latin-Illyrian families and was a nation in its own right. It was also made up of many ethnic nationalities.[47][48][49][50] As a Maritime nation it traded all over the Mediterranean and even had trade with the Americas.

Editor's Note on Old Dubrovnik

The research I have done in the last three years has led me to this conclusion concerning the history of Dubrovnik area (for now anyway.... I'm always open to new information).

Conclusion

The ancient peoples of Dubrovnik identified themselves as Ragusans. Latin-Illyrian families created the Republic of Ragusa. Modern theories say that a small town was already there during the times of the Roman Empire (some say even earlier).[51]

Refugees from Roman Epidaurus in the 7th century turned it into a fortified city. Over the centuries, it became a City State importantly called Ragusa. Later it became a Republic (1358), also importantly called Republic of Ragusa. The early medieval City State had a population of Romans and Latinized Illyrians, who spoke Latin. With time it evolved into the Dalmatian language (Ragusan Dalmatian) , a now extinct Romance language. The Ragusan Dalmatian language disappeared in the 17th century.[52] For centuries Ragusa, was an Italian-City State.

In the 16th and 17th century a large proportion of its ethnic population changed dramatically mainly due to various historical events in Europe (as the Ottoman Empire advanced into Europe migrations from the east started (i.e new Croatians, Serbs, Albanians etc,). From the west Spanish Jews (Spanish-Jews were expelled in 1493 from Spain). The Republic became a hub of multi-ethnic communities. The most numerous of these were the Slavs (according to Francesco Maria Appendini, Slavic was being spoken in Ragusa already in the 13th century [53][54]). The peoples of the Republic started to merge (including mixed marriages). Additionally the Ragusan-Slavic population were Romanised, meaning they adopted Latin Mediterranean culture. A form of Italian was spoken in the Republic, which was heavily influenced by Venetian. Books were written in Latin and Italian. Some Ragusans started to write in a Slavic language. Two languages Italian and Slavic (which at times overlapped) became the norm in the Republic.

During the Napoleonic Wars the "Republic of Ragusa" ceased to be and It became part of Napoleon's French Empire in 1808. In 1815 it was made a part of the Habsburg Empire (later renamed the Austro-Hungarian Empire). The former Republic was within the province of the Kingdom of Dalmatia and under Austrian rule. In essence the Republic's borders collapsed and was occupied. With the opening up of the Republic's borders, peoples who were once foreigners (or even enemies), were now citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The political situation started to change and this was in part due to the nationalistic movements of the 19th century. In the neighbouring Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia a Croatian nationalistic movement was established and alongside that, within the Balkan region a Pan-Slavic movement was growing (the beginnings of the ill fated Yugoslavia). These political on goings started to be felt in the Kingdom of Dalmatia. The Austrians in the 1860s started to introduce within the Kingdom of Dalmatia a standardised Croatian language originally referred to as Illirski.[55] It then replaced Italian altogether. In effect the government undertook culture genocide. [56] For centuries the Italian language was the official language of the Dalmatian establishment. It was also the spoken language in white-collar, civil service and merchant families. [57]

The process of creating a standardised Croatian language was incomplete. This is reflected in its labelling of the language as Croatian, Croatian-Serbo and the very unpopular Serbo-Croatian. This was a fundamental mistake made when political extremist ideology influenced decision-making regarding language and culture. It was an attempt at imitating Western imperial empire building egotism (a super Southern Slav State), which failed. [58][59]

A process of Croatisation (cultural assimilation) of the Republic of Ragusa's history began in the 19th century (and in part the Kingdom of Dalmatia) and this process is still continuing today. This process happened firstly in relation to the Ragusan-Slavic history and later with the Ragusan-Italianic history. In relation to this Croatisation of history,

- Gianfrancesco Gondola (1589 -1638) a Ragusan Baroque poet from Republic of Ragusa - now has become a ...........

- Croatian Baroque poet called Ivan Gundulić from Dubrovnik, Croatia.

Ivan Gundulic wrote many works in Italian and Croatian (previously referred to as Slavic).

One of these was the Slavic poem Osman. Interestingly, in a 1826 publication his name was written Giva Gundulichja and in 1967 his work was referred to as:

Quote taken from the book Dubrovnik by Bariša Krekić[60]

Additionally Italian and Serbian communities both try to claim Republic of Ragusa-Dubrovnik's cultural history.

See also

External links

- Image of Zadar post Allied bombings (February 4th 1944)

- Dalmatian Language (Wikipedia)

- Wikipedia: Battle of Curzola

- The Italians of Dalmatia: From Italian Unification to World War I written by Luciano Monzali:

"Located on the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea, the area known as Dalmatia, part of modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, was part of the Austrian Empire during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Dalmatia was a multicultural region that had traditionally been politically and economically dominated by its Italian minority. In The Italians of Dalmatia , Luciano Monzali argues that the vast majority of local Italians were loyal to and supportive of Habsburg rule, desiring only a larger degree of local autonomy."

Notes and References

- ^ Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Volume 3 by Dinah Shelton Macmillan Reference, 2005 - Political Science (p.1170)

- "Native German and Hungarian communities, seen as complicit with wartime occupation, were brutally treated; tantamount in some cases to ethnic cleansing. The Volksdeutsch settlements of Vojvodina and Slavonia largely disappeared. Perhaps 100,000 people—half the ethnic German population in Yugoslavia—fled in 1945, and many who remained were compelled to do forced labor, murdered, or later ransomed by West Germany. Some 20,000 Hungarians of Vojvodina were killed in reprisals. Albanian rebellions in Kosovo were suppressed, with prisoners sent on death marches towards the coast. An estimated 170,000 ethnic Italians fled to Italy in the late 1940s and 1950s. (All of these figures are highly approximate.)"

- ^ The Frontiers of Europe by Malcolm Anderson & Eberhard Bort (p77)

- ^ History in Exile: Memory and Identity at the Borders of the Balkans by Pamela Ballinger (p155)

- ^ Volkszählung vom 31. Dezember 1910, veröffentlicht in: Geographischer Atlas zur Vaterlandskunde an der österreichischen Mittelschulen. K. u. k. Hof-Kartographische Anstalt G. Freytag & Berndt, Wien 1911.

- ^ A London Encyclopaedia: Or Universal Dictionary of Science, Art, Literature (p48)

- "In the latter ages of the Roman Empire this country suffered frequently from in-roads of Barbarians..."

- ^ The Changing Face of Dalmatia: Archaeological and Ecological Studies in a Mediterranean landscape by John Chapman, Robert Shiel & Sime Batovic

- "In chapters 29 and 30, two similar accounts are given for the fall of nearby Salona to the Avars and Slavs ..."

- ^ The Italians of Dalmatia: From Italian Unification to World War One by Luciano Monzali (p5)

- ^ Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia by Danijel Dzino (p212).

- ^ Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia by Danijel Dzino (p52).

- ^ The Illyrians by John Wilkes (p269)

- ^ Dalmatian Language (Wikipedia)

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe by Glanville Price (p377)

- ^ University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies-The Slavonic Latin Symbiosis in Dalmatia during the Middle Ages by Victor Novak

- ^ The Extraterrestrial Life Debate, 1750-1900 by Michael J. Crowe (p.156)

- ^ With the Serbian forces being annihilated in the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 a migration of peoples stated to migrant west ward. Dalmatia started acquire new peoples in its region (i.e. Croatians, Serbs & Albanians).

- ^ The Hvar Rebellion (1510 - 1514) was an uprising of the people and citizens of the Venetian Dalmatia island of Hvar (Lissa) against the island's nobility and their Venetian masters.

- ^ The Italians of Dalmatia: From Italian Unification to World War One by Luciano Monzali (p8)

- ^ www.discover-montenegro.com/perast.htm

- ^ Venice and the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenment by Larry Wolff (p312-p313)

- ^ Balkan Babel: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia from the Death of Tito to the Fall of Milosevic by Sabrina P. Ramet. Note: Croatisation is a form of Slavicisation.

- ^ Croatisation or Slavicisation was a policy firstly implemented under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- ^ Medieval Greek"Dalmatae": Δαλμᾶται.

- ^ Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a journey to Mostar in Herzegovina.Volume 1 by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (p4)

- ^ Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a journey to Mostar in Herzegovina.Volume 1 by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (p362)

- ^ Researches on the Danube and the Adriatic, Volume 1 by Andrew Archibald Paton (p167)

- ^ Dalmatia: The Land Where East Meets West by Maude Holbach (p121)

- "DALMATIA: The Land Where East Meets West is MAUDE M. HOLBACH's second book of travel in Eastern Europe. First published in 1910, this is an anthropological travel journal of an often-overlooked kingdom"

- ^ The Italians of Dalmatia: From Italian Unification to World War I by Luciano Monzali (p65)

- ^ The Italians of Dalmatia:From Italian Unification to World War I by Luciano Monzali (p102)

- ^ A.Bajamonti, Discorso inaugurale della Società Politica dalmata, Spalato 1886

- ^ Refugees in the Age of Total War by Anna Bramwell (p136, read Zara-p137)

- ^ A Tragedy Revealed The Story of the Italian Population of Istria & Dalmatia by Arrigo Petacco. (p12 & read page 81 Zadar/Zara)

- ^ secretdalmatia.wordpress.com/2010/11/24/zadar-the-charming-past

- ^ www.italianlives.arts.uwa.edu.au/stories/martini/background The University of Western Australia, http://www.italianlives.arts.uwa.edu.au LINK: http://www.italianlives.arts.uwa.edu.au/stories/martini/background

- ^ European Public Hearing on “Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes" (p201)

- ^ “Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regime-Brussels"

- ^ The Fragmentation of Yugoslavia: Nationalism and War in the Balkans by Aleksandar Pavkovic (p 47).

- The former Yugoslavia's political and cultural scene were heavily influenced by the cult of personality of the Dictator Josip Broz Tito.

- ^ Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia by Danijel Dzino (p43)

- ^ When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans: by John Van Antwerp Fine (p11)

- ^ When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans by John Van Antwerp Fine (p15)

- ^ Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia by Danijel Dzino (p20)

- ^ Dalmatia (History, Culture, Art Heritage) by Antun Travirka (p137)

- ^ Editors note: Recent DNA studies have stated that more than three quarters of today's Croatian men are the descendants of Europeans who inhabited Europe 13 000-20 000 years ago. The first primary source (factual-that its authenticity isn't disputed) to mention the Croatian-Hrvat identity in the Balkans was Duke Branimir (Latin: "Branimiro comite dux cruatorum cogitavit" c. 880 AD). Branimir was a Slav from Dalmatia. Prior to the arrival of the Slavs, Roman Dalmatia was mainly inhabited by a Roman Latin-Illyrian population.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica (publ. 1911)

- ^ ""Croatia." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. 09 Mar. 2011." (2011). Archived from the original on 2012-05-24. Retrieved on 2011-03-8.

- ^ Dalmatia (History, Culture, Art Heritage) by Antun Travirka (p141)

- ^ When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans: by John Van Antwerp Fine (p157)

- ^ Croatia by Michael Schuman (p82)

- ^ Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Mediterranean World after 1492 By Alisa Meyuhas Ginio (p190)

- ^ The Chicago Jewish forum, Volume 23 by Benjamin Weintroub (p271)

- ^ Footprint Croatia by Jane Foster

- ^ Note: Recent findings of artefacts in Dubrovnik suggest to be Greek in origin.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Note: According to Francesco Maria Appendini (Italian scholar from Dubrovnik 1768–1837) the Slavic language already started to be spoken in area in the 13th century. The Charter of Ban Kulin (1189) mentions Dubrovьcane, meaning people from Dubrovnik (Ragusa)

- ^ When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans: by John Van Antwerp Fine (p229)

- "Discussions between Ottoman officials (many of whom were of Slavic origin) and Ragusan envoys were frequently carried out in “our language” (proto- Serbo- Croatian), and both sides (these particular Ottomans and the Ragusan diplomats)" Editors Note: This event as described by John Van Antwerp Fine is from 1608.

- ^ Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (an 19 century English historian. October 5, 1797 – October 29, 1875)

- He too referred to the Dalmatian Slavic dialect as Illirskee. Cited from Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a Journey to Mostar in Herzegovina by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson. (p33)

- ^ The Italians of Dalmatia From Italian Unification to World War I by Luciano Monzali (p83)

- One of the last Italian school that was abolished was in Korčula (Curzola) on the 13th of September 1876.

- ^ Osnovna Škola "Vela Luka" Vela Luka Zbornik-150 Godina Školstva u Velaoj Luci (in Croatian-p8)

- The Early Beginnings of Formal Education - Vela Luka (beginnings of literacy and Lower Primary School 1857 – 1870):

- ^ Language and Identity in the Balkans: Serbo-Croatian and Its Disintegration ... By Robert D. Greenberg

- ^ LANGUAGE AND NATION: AN ANALYSIS OF CROATIAN LINGUISTIC NATIONALISM - A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State (p43)

- ^ Dubrovnik by Bariša Krekić "The works of the greatest poet of early Yugoslav literature, Ivan Gundulic, 1589 — 1638, are the best testimony to this. His epic "Osman" ranks among the greatest masterpieces of early Slavic literature, and also among the most ..."

This article is a work in progress. Sections of the article is transferred from Wikipedia.

"[Country_Code" contains a listed "[" character as part of the property label and has therefore been classified as invalid. "[Country_Code" contains a listed "[" character as part of the property label and has therefore been classified as invalid. Dalmatia Dalmatian Language Dalmatian Venetian Zadar Split Dubrovnik Roman Dalmatia Dalmatia Italy Dalmatia Antun Travirka Dalmatia History, Culture, Art Heritage Venetian Dalmatia Antonio Bajamonti Roger Joseph Boscovich Republic of Ragusa Dalmatian History Yugoslavia biased ultra nationalistic propaganda biased ultra nationalistic propaganda cultural genocide cultural genocide Defaced Photo by Peter Zuvela |