Croatisation

Croatisation is a term used to describe a process of cultural assimilation, and its consequences, in which people or lands ethnically partially Croat or non Croat become voluntary or forced Croat.

Croatisation of Serbs

Serbs have been victims of Croatisation throughout history.

Uskoks

A large part of the Habsburg unit of Uskoks, who fought a guerilla war with the Ottoman Empire were ethnic Serbs (Serbian Orthodox Christian) who fled from Ottoman Turkish rule and settled in Bela Krajina and Zumberak.[1][2][3][4]

Serbs of Croatia in the Roman Catholic-Croatian Military Frontier were out of the jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć and in 1611, after demands from the community, the Pope establishes the Eparchy of Marca (Vratanija) with seat at the Serbian-built Marca Monastery and instates a Byzantine vicar as bishop sub-ordinate to the Roman Catholic bishop of Zagreb, working to bring Serbian Orthodox Christians into communion with Rome which caused struggle of power between the Catholics and the Serbs over the region. In 1695 Serbian Orthodox Eparchy of Lika-Krbava and Zrinopolje is established by metropolitan Atanasije Ljubojevic and certified by Emperor Josef I in 1707. In 1735 the Serbian Orthodox protested in the Marča Monastery and becomes part of the Serbian Orthodox Church until 1753 when the Pope restores the Roman Catholic clergy. On June 17, 1777 the Eparchy of Križevci is permanently established by Pope Pius VI with see at Križevci, near Zagreb, thus forming the Croatian Greek Catholic Church which would after World War I include other people; Rusyns and Ukrainians of Yugoslavia.[3][4]

Catholic Croats of Turopolje and Gornja Stubica celebrate the Jurjevo, a Serbian tradition maintained by Uskoks descendants.

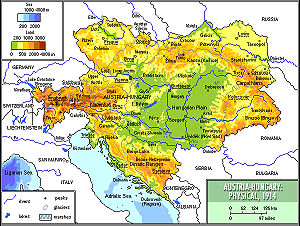

Croatia in the Austro-Hungarian Empire

In the early 19th century, Croatia was a part of the Habsburg Monarchy (later known as Austro-Hungarian Empire). As the wave of romantic nationalism swept across Europe, the Croatian capital, Zagreb, became the centre of a national revival that became known as the Illyrian Movement. Although it was initiated by Croatian intellectuals, it promoted the brotherhood of all Slavic peoples. For this reason, many intellectuals from other Slavic countries or from the minority groups within Croatia flocked to Zagreb to participate in the undertaking. In the process, they voluntarily assumed a Croatian identity, i.e., became Croatised, some even changing their names into Croatian counterparts and converted to Roman Catholicism, notably the Serbs

Croatisation in the NDH

The Croatisation during Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was aimed primarily to Serbs, with Italian, Jews and Roma to a lesser degree. The Ustase aim was a "pure Croatia" and the biggest enemy was the ethnic Serbs of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ministers announced the goals and strategies of the Ustaše in May 1941. The same statements and similar or related ones were also repeated in public speeches by single ministers as Mile Budak in Gospic and, a month later, by Mladen Lorkovic.[5]

- One third of the Serbs (in the Independent State of Croatia) were to be forcibly converted to Catholicism.

- One third of the Serbs were to be expelled (ethnically cleansed).

- One third of the Serbs were to be killed.

Croatisation of Italy's Julian March and Zadar

Even with a predominant Croatian majority, Dalmatia retained relatively large Italian communities in the coast (Italian majority in some cities and islands, largest concentration in Istria). Italians in Dalmatia kept key political positions and Croatian majority had to make an enormous effort to get Croatian language into schools and offices. Most Dalmatian Italians gradually assimilated to the prevailing Croatian culture and language between the 1860s and World War I, although Italian language and culture remained present in Dalmatia. The community was granted minority rights in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia; during the Italian occupation of Dalmatia in World War II, it was caught in the ethnic violence towards non-Italians during fascist repression: what remained of the community fled the area after World War II. [6]

The history took its turn: while from 1919. - 1945. Italian Fascists stated by the proclamation that all Croatian and other non-Italian surnames must be turned to Italian ones (which they had chosen for every surname, so Anić became Anetti, Babačić Babetti etc.; 115.157 Croats and other non-Italians were forced to change their surname), the Italian community of Istria and Dalmatia were forced to change their names to Croats and Yugoslav, during Tito's Yugoslavia.[7][8]

The same happened - but with lower incidence - with Italians in Istria and Rijeka (Fiume) who were the majority of the population in most of the coastal areas in the first half of the 19th century, while at the beginning of World War I they numbered less than 50%.

After World War II most of the Italians left Istria and the cities of Italian Dalmatia in the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus.[9] The remaining Italians were forced to be assimilated culturally and even linguistically during Josip Broz Tito's rule of communist Yugoslavia.[10][11] Following the exodus, the areas were settled and heavily croatized with Yugoslav people.[11][12] Economic insecurity, ethnic hatred and the international political context that eventually led to the Iron Curtain resulted in up to 350,000 people, mostly Italians, forced to leave the region. The London Memorandum (1954) gave the ethnic Italians the choice of either leaving (the so-called optants) or staying. These exiles would have been to be given compensation for their loss of property and other indemnity by the Italian state under the terms of the peace treaties. Those opted to stay had to suffer a slow but forced croatisation.[13]

Some sporadic Croatization phenomena still took place in the last years of 20th century after Croatian Indipendency, despites many towns were declared bilingual by Croatian Law.[14][15]

During and prior to the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Following the establishment of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia in November 1991, and especially from May 1992 forward, the Herzeg-Bosnia leadership engaged in continuing and coordinated efforts to dominate and "Croatise" (or ethnically cleanse) the municipalities which they claimed were part of Herzeg-Bosnia, with increasing persecution and discrimination directed against the Bosniak population.[16] The Croatian Defence Council (HVO), the military formation of Croats, took control of many municipal governments and services, removing or marginalising local Bosniak leaders.[17] Herzeg-Bosnia authorities and Croat military forces took control of the media and imposed Croatian ideas and propaganda.[18] Croatian symbols and currency were introduced, and Croatian curricula and the Croatian language were introduced in schools. Many Bosniaks were removed from positions in government and private business; humanitarian aid was managed and distributed to the Bosniaks' disadvantage; and Bosniaks in general were increasingly harassed. Many of them were deported to concentration camps: Heliodrom, Dretelj, Gabela, Vojno, and Šunje.

Notable individuals who voluntarily Croatised

- Dimitrija Demeter, a playwright who was the author of the first modern Croatian drama, was from a Greek family.

- Vatroslav Lisinski, a composer, was originally named Ignaz Fuchs. His Croatian name is a literal translation.

- Laval Nugent, a Field Marshall and the most powerful noble in the Illyrian Movement, was originally from Ireland.

- Petar Preradović, one of the most influential poets of the movement, was from a Serb family.

- Bogoslav Šulek, a lexicographer and inventor of many Croatian scientific terms, was originally Bohuslav Šulek from Slovakia.

- Stanko Vraz, a poet and the first professional writer in Croatia, was originally Jakob Frass from Slovenia.

- August Šenoa, a Croatian novelist, poet and writer, is of Czech-Slovak descent. His parents never learned the Croatian language, even when they lived in Zagreb.

- Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger, a geologist, palaeontologist and archaeologist who discovered Krapina man[19] (Krapinski pračovjek), was of German descent. He added his second name, Gorjanović, to be adopted as a Croatian.

- Slavoljub Eduard Penkala was an inventor of Dutch/Polish origins. He added the name Slavoljub in order to Croatise.

- Lovro Monti, Croatian politician, mayor of Knin. One of the leaders of the Croatian national movement in Dalmatia, he was of Italian roots.

- Adolfo Veber Tkalčević -linguist of German descent.

- Ivan Zajc (born Giovanni von Seitz) a music composer was of German descent.

- Josip Frank, nationalist Croatian 19th century politicia, born as a Jew.

- Vladko Maček, Croatian politician, leader of the Croats in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia after Stjepan Radić and one time opposition reformist, maker of the Cvetković-Maček agreement that founded the Croatian Banate, born in a Slovene-Czech family.

- Savić Marković Štedimlija, publicist and Nazi collaborator, Montenegrin by origin.

- Vlaho Bukovac, born Biagio Faggioni to a family of mixed Italian and Croatian ancestry.

Editor's Note

A process of Croatisation (cultural assimilation) of the Republic of Ragusa's history (and in part the Kingdom of Dalmatia) began in the 19th century and this process is still continuing today. This process happened firstly in relation to the Ragusan-Slavic history and later with the Ragusan-Italianic history. In relation to this Croatisation of history, Gianfrancesco Gondola (1589 -1638) a Ragusan Baroque poet from Republic of Ragusa has become a Croatian Baroque poet called Ivan Gundulić from Dubrovnik, Croatia. Ivan Gundulic wrote many works in Italian and Slavic (today referred to as Croatian[20]).

One of these was the Slavic poem Osman. Interestingly, in 1967 his work was referred to as "The works of the greatest poet of early Yugoslav literature, Ivan Gundulić" taken from the book Dubrovnik by Bariša Krekić[21]

The ancient peoples of Dubrovnik identified themselves as Ragusans. Latin-Illyrian families created the Republic of Ragusa. Modern theories say that a small town was already there during the times of the Roman Empire (some say even earlier).[22]

Refugees from Roman Epidaurus in the 7th century turned it into a fortified city. Over the centuries, it became a City State importantly called Ragusa. Later it became a Republic (1358), also importantly called Republic of Ragusa. The early medieval City State had a population of Romans and Latinized Illyrians, who spoke Latin. With time it evolved into the Dalmatian language, a now extinct Romance language. The Ragusan Dalmatian language disappeared in the 17th century. For centuries Ragusa, was an Italian-City State.

In the 16th and 17th century [23][24] its ethnic population changed dramatically mainly due to various historical events in Europe. It became a hub of multi-ethnic communities. The most numerous of these were the Slavs. The peoples of the Republic started to merge (including mixed marriages). Additionally the Ragusan-Slavic population were Romanised, meaning they adopted Latin Mediterranean culture. A form of Italian was spoken in the Republic, which was heavily influenced by Venetian. Books were written in Latin and Italian. Some Ragusans started to write in a Slavic language. Two languages Italian and Slavic (which at times overlapped) became the norm in the Republic.

- Statement made by the contemporary historian John Van Antwerp Fine (Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Michigan, USA):

| “ | This is not surprising since the “Ragusans” identified themselves as Ragusans and not as Croats.[25] | ” |

During the Napoleonic Wars the "Republic of Ragusa" ceased to be. In 1815 it was made a part of the Habsburg Empire (later renamed the Austro-Hungarian Empire). The former Republic was within the province of the Kingdom of Dalmatia and under Austrian rule. In essence it was occupied. Former Republic of Ragusa borders were opened up. Peoples who were once foreigners (even enemies), were now citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The political situation stated to change and one of them was the nationalistic movement of the 19th century. In the neighbouring Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia a Croatian nationalistic movement was established and alongside that, within the Balkan region a Pan-Slavic movement was growing (the beginnings of the ill fated Yugoslavia). These political on goings started to be felt in the Kingdom of Dalmatia. The Austrians in the 1860s started to introduce within the Kingdom of Dalmatia a standardised Croatian language sometimes referred to as Illirski.[26] It then replaced Italian altogether. In effect the government undertook culture genocide. For centuries the Italian language was the official language of the Dalmatian establishment. It was also the spoken language in white-collar, civil service and merchant families. [27]

The process of creating a standardised Croatian language was incomplete. This is reflected in its labelling of the language as Croatian, Croatian-Serbo and the very unpopular Serbo-Croatian. This was a fundamental mistake made when political extremist ideology influenced decision-making regarding language and culture. It was an attempt at imitating Western imperial empire building egotism (a super Southern Slav State), which failed. [28]

- Statements made by the contemporary historian John Van Antwerp Fine (Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Michigan) on ethnic ambitions and Croatian historians:

| “ | Such substitutions of “Croat” for” Slav,” however, mislead the reader into believing something the sources do not tell...[29]

|

” |

Notes and References

- ^ Europe:A History by Norman Davies (1996), p. 561.

- ^ Goffman (2002), p. 190.

- ^ a b http://books.google.se/books?id=ovCVDLYN_JgC

- ^ a b http://books.google.se/books?id=0pmkrY29qkIC

- ^ Eric Gobetti, "L' occupazione allegra. Gli italiani in Jugoslavia (1941-1943)", Carocci, 2007, 260 pages; ISBN 8843041711, ISBN 9788843041718, quoting from V. Novak, Sarajevo 1964 and Savez jevrejskih opstina FNR Jugoslavije, Beograd 1952

- ^ Društvo književnika Hrvatske, Bridge, Volume 1995, Nubers 9-10, Croatian literature series - Ministarstvo kulture, Croatian Writer's Association, 1989

- ^ Nenad Vekarić, Pelješki rodovi, Vol. 2, HAZU, 1996 - ISBN 9789531540322

- ^ Jasminka Udovički and James Ridgeway, Burn this house: the making and unmaking of Yugoslavia

- ^ Several estimates of the Istrian-Julian exodus by historians:

- Vladimir Žerjavić (Croat), 191,421 Italian exiles from Croatian territory.

- Nevenka Troha (Slovene), 40,000 Italian and 3,000 Slovene exiles from Croatian and Slovenian territory.

- Raoul Pupo (Italian), about 250,000 Italian exiles

- Flaminio Rocchi (Italian), about 350,000 Italian exiles

- The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission verified 27,000 Italian and 3,000 Slovene migrants from Croatian and Slovenian territory.

- ^ Luciano Monzali, Antonio Tacconi e la comunità italiana di Spalato, Società dalmata di storia patria.

- ^ a b <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>Darko Darovec. "THE PERIOD OF TOTALITARIAN RÉGIMES - The Reasons for the Exodus".

- ^ Liliana Ferrari, Essay on Raoul Pupo, pag. 5, Rizzoli, Gorizia 2005

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet, Balkan babel: the disintegration of Yugoslavia from the death of Tito, Westview Press, 2002 «...and since the sixties, those of the rest of Croatia. The Istrian Democratic Party demanded autonomy for Istria, as a protection against "the forcible Croatization of Istria" and an imposition of a coarse and fanatical Croatism[...] Furio Radin argued that such autonomy was vital for the cultural protection of the Italian minority in Istria.»

- ^ «Pola, no to Italian chorus in St. Anthony church» in "Difesa Adriatica" year XIV n.5 - may 2008

- ^ Alex J. Bellamy, he formation of Croatian national identity, Manchester University Press, 2003, ISBN 9780719065026

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"ICTY: Blaškić verdict - A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993 c) The municipality of Kiseljak".

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"ICTY: Blaškić verdict - A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993 - b) The municipality of Busovača".

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"ICTY: Blaškić verdict — A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993 - c) The municipality of Kiseljak".

the authorities created a radio station which broadcast nationalist propaganda

- ^ Krapina C

- ^ ""Dubrovnik." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. 08 Mar. 2011." (2011). Retrieved on 2011-03-8.

- ^ Dubrovnik by Bariša Krekić "The works of the greatest poet of early Yugoslav literature, Ivan Gundulic, 1589 — 1638, are the best testimony to this. His epic "Osman" ranks among the greatest masterpieces of early Slavic literature, and also among the most ..."

- ^ Note: Recent findings of artefacts in Dubrovnik suggest to be Greek in origin.

- ^ When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans: by John Van Antwerp Fine (p229)

- "Discussions between Ottoman officials (many of whom were of Slavic origin) and Ragusan envoys were frequently carried out in “our language” (proto- Serbo- Croatian), and both sides (these particular Ottomans and the Ragusan diplomats)" Editors Note: These event describe by John Van Antwerp Fine are from 1608.

- ^ Note: According to Francesco Maria Appendini (Italian scholar 1768–1837) the Slavic language started to be spoken in area in the 13th century.

- ^ When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans: by John Van Antwerp Fine (p157)

- ^ Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (an 19 century English historian. October 5, 1797 – October 29, 1875)

- He too referred to the Dalmatian Slavic dialect as Illirskee. Cited from Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a Journey to Mostar in Herzegovina by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson. (p33)

- ^ Osnovna Škola "Vela Luka" Vela Luka Zbornik-150 Godina Školstva u Velaoj Luci (in Croatian-p8)

- The Early Beginnings of Formal Education - Vela Luka (beginnings of literacy and Lower Primary School 1857 – 1870):

- ^ LANGUAGE AND NATION: AN ANALYSIS OF CROATIAN LINGUISTIC NATIONALISM - A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State (p43)

“ Robert Greenberg, the foremost English-language scholar on South Slav languages, believes the root of the language polemic lies in the Vienna agreement of 1850, which “reversed several centuries of natural Abstand developments for the languages of Orthodox Southern Slavs and Catholic Southern Slavs.” (Greenberg 2004, 23) Croatians and Serbians came to the negotiating table with differing experiences. Serbian linguists were standardizing a single dialect of rural speech and breaking with the archaic Slaveno-Serbian heritage of the eighteenth century “Serbian enlightenment.” Early Croat nationalists proposed a standard language based on a widely spoken dialect linked with the literature of the Croatian Renaissance. With an eye towards South Slav unity they also encouraged liberal borrowing from various dialects (Greenberg 2004, 24-26). This basic difference in approach created conflicts throughout the history of the South Slav movement and the Yugoslav state (Greenberg 2004, 48). ” - ^ When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans: by John Van Antwerp Fine (p11)

- ^ When Ethnicity did not Matter in the Balkans by John Van Antwerp Fine (p15)

See also

External links

- croatiepolcroa.htm

- www.serbianunity.net

- www.aimpress.ch

- http://www.southeasteurope.org/subpage.php?sub_site=2&id=16431&head=if&site=4

- http://www.nouvelle-europe.eu/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=172&Itemid=

- http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=18696

- http://www.gimnazija.hr/?200_godina_gimnazije:OD_1897._DO_1921.

- http://www.hdpz.htnet.hr/broj186/jonjic2.htm

This article is a work in progress. Sections of the article is transferred from Wikipedia.

|

<sharethis />