Fausto Veranzio

This is about Wikipedia's article on Fausto Veranzio.

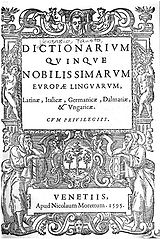

Fausto Veranzio is another article on Wikipedia that exhibits nationalistic editing. Fausto Veranzio (or Faust Vrancic) [1] was historically a citizen of the Republic of Venice in the 16th and 17th century. He does have a Croatian background through family lineage.[2] He was a brilliant scientist in his day and is noted for his invention of the parachute.[3]

| “ | Wikipedia states: ... he was a polymath and bishop from Croatia. [4] (3rd of October 2010) | ” |

It must be stated that this man was from the Republic of Venice not from Croatia, in fact Croatia did not exist as a sovereign state for at least three hundred years after his time.

This is using Wikipedia for nationalistic propaganda and is not based on fact. It otherwise tainted a perfectly good article on this unique individual. Fausto was born in Sibenik circa 1551 in Dalmatia, a region of the Republic of Venice in todays modern Croatia. In the 19th century Dalmatia became a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Dalmatia as a province, dates back to the Roman Empire [5] and is several centuries older that Croatia itself.

Note: Fausto Veranzio in 1617, (sixty-five years old) implemented his design and tested the parachute by jumping from St Mark's Campanile in Venice. Today a Croatian Navy rescue ship bears the name Faust Vrančić.

- Encyclopedia Britannica-Dalmatia:

| “ |

|

” |

References concerning Dalmatian

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1797 – 1875) was an English traveller, writer and pioneer Egyptologist of the 19th century. He is often referred to as "the Father of British Egyptology". He was in Dubrovnik (then called Ragusa) in 1848, he wrote in his; Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a Journey to Mostar in Herzegovina.Volume 1:

| “ | Italian is spoken in all the seaports of Dalmatia, but the language of the country is a dialect of the Slavonic, which alone is used by peasants in the interior. [8] | ” |

| “ | Their language though gradually falling into Venetianisms of the other Dalmatians towns, still retains some of that pure Italian idiom, for which was always noted. [9] | ” |

Andrew Archibald Paton

Andrew Archibald Paton (1811 - 1874) was a British diplomat and writer from the 19 century. In 1861 he wrote in his; Researches on the Danube and the Adriatic: Or, Contributions to the Modern:

| “ | Signor Arneri (from Korcula) stated: These three pears you see on the wall," said he, "are the arms of my family. Perussich (Piruzović) [10] was the name, when, in the earlier part of the fifteenth century, my ancestors built this palace; so that, you see.

I am Dalmatian. All the family, fathers, sons, and brothers, used to serve in the fleets of the Republic (Republic of Venice); but the hero of our race was Arneri Perussich, whose statue you see there, who fought, bled, and died at the Siege of Candia, whose memory was honoured by the Republic, and whose surviving family was liberally pensioned; so his name of our race. We became Arneri, and ceased to be Perussich. [11] |

” |

Maude Holbach (a 1910 travel guide)

- Dalmatia-The Land Where East Meets West by Maude Holbach (a 1910 travel guide from COSIMO books and publications New York USA):

| “ | Two hundred years later that, is, early in the tenth century you might have heard Slavish and Latin spoken had you walked in the streets of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), just as you hear Slavish and Italian today; for as times of peace followed times of war, the Greek and Roman inhabitants of Rausium intermarried with the surrounding Slavs, and so a mixed race sprang up, a people apart from the rest of Dalmatia. [12] | ” |

See also

- The Wikipedia Point of View

- The Wikipedia Point of View/Activists

- Worst of Wikipedia

- Top 10 Reasons Not to Donate to Wikipedia

References

- ^ Pronounced in Croatian: Vranchic or Vrančić

- ^ Travels Into Dalmatia by Abbe Alberto Fortis (p121)

- ^ He's in the Paratroops Now by Alfred Day Rathbone (p172)

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"Wikipedia: Fausto Veranzio". 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-04. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume 1 by Edward Gibbon (p158)

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"Encyclopedia Britannica: Ladislas". 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-06

- "Ladislas, (1377—1414, Naples), king of Naples (from 1386), claimant to the throne of Hungary (from 1390), and prince of Taranto (from 1406). He became a skilled political and military leader, taking advantage of power struggles on the Italian peninsula to greatly expand his kingdom and his power. Succeeding his father, Charles III, in 1386, Ladislas was king at age nine under the regency of his mother, Margaret of Durazzo. Expelled from Naples in 1387 by the rival claimant Louis II of Anjou, he first subdued the recalcitrant Neapolitan barons". line feed character in

|accessdate=at position 11 (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)

- "Ladislas, (1377—1414, Naples), king of Naples (from 1386), claimant to the throne of Hungary (from 1390), and prince of Taranto (from 1406). He became a skilled political and military leader, taking advantage of power struggles on the Italian peninsula to greatly expand his kingdom and his power. Succeeding his father, Charles III, in 1386, Ladislas was king at age nine under the regency of his mother, Margaret of Durazzo. Expelled from Naples in 1387 by the rival claimant Louis II of Anjou, he first subdued the recalcitrant Neapolitan barons". line feed character in

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica: Dalmatia

- ^ Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a journey to Mostar in Herzegovina.Volume 1 by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (p4)

- ^ Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a journey to Mostar in Herzegovina.Volume 1 by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (p362)

- ^ Otok Korčula (2nd edition) by Marinko Gjivoje, Zagreb 1969.

- According to Marinko Gjivoje: Perussich is Piruzović. (p46-p47)

- The book outlines A-Z about the island of Korcula (Corzula), from traditions, history, culture to wildlife, politics & geography.

- ^ Researches on the Danube and the Adriatic: by Andrew Archibald Paton. Chapter 4. The Dalmatian Archipelago.(p164)

- ^ Dalmatia: The Land Where East Meets West by Maude Holbach (p121)

- "DALMATIA: The Land Where East Meets West is MAUDE M. HOLBACH's second book of travel in Eastern Europe. First published in 1910, this is an anthropological travel journal of an often-overlooked kingdom" Web site: www.cosimobooks.com

External links

- Francesco Patrizi: BEYOND NECESSITY- Francesco Patrizi link

The case of Francesco Patrizi, the Venetian philosopher, is a fine illustration of the nationalistic warfare that infests Wikipedia, and the inaccuracy and distortion and bias that follows as a result.

| “ | Quote by Ocham-London, United Kingdom:The problem becomes particularly acute in a place like Wikipedia, where the only intellectual interest - that is to say, no intellectual interest at all - lies simply in a nationalistic dispute, in this case between Italians and Croatians. | ” |

- Veranzio's, Machinae Novae (Venice 1595) contained designs of 56 different machines, tools, devices and technical concepts.Two variants of this work exist, one with the "Declaratio" in Latin and Italian. The book was written in Italian, Spanish, French and German. Veranzio died in Venice in 1617 and was buried in Dalmatia, near by his family's country-house.

<sharethis />