Split Riots

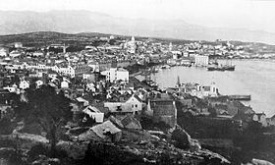

In 1918–1920, a series of riots took place in the city of Spalato, today called Split [1] which is now part of modern Croatia. The city was officially called "Split" only after the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. The incident was between Dalmatian Italians and local Slavs fighting for the control of the city.

Political background

The Riots of Spalato were a group of violent events, related to anti-italianism that happened in Split between 1918 and 1920 and that resulted in the killing of Captain Tommaso Gulli of the Italian navy ship "Puglia" (and a sailor named Aldo Rossi). He was hit on July 11, 1920 and was dead the next morning.

These battles belong to a centuries-long struggle for the control of the Adriatic eastern coast between Slavs (mainly Croats and Slovenians) and Italians. This struggle hugely increased during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when the Italian irredentism and the Slavic nationalism at the end of the XIX century created a bloody confrontation in the Adriatic area.

Indeed, during the second half of the XIX century in Split there was a continuing struggle between the Autonomist Party (Dalmatia) pro-Italians and the Narodnjaci (People's Party-Dalmatia) pro-Slavs. The last Italian major was Antonio Bajamonti. The city from 1882 had experienced a process of Croatisation. Bajamonti, the most prominent Dalmatian Italian in history, once remarked:

| “ | No joy, only pain and tears, is brought by being a part of the Italian Party in Dalmatia. We, the Italians of Dalmatia, retain a single right to suffer.[2] | ” |

The Narodnjaci

- The National Party (Narodnjaci-People's Party) from the Kingdom of Dalmatia (part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) stated:

| “ | According to Costant (Kosta) Vojnovic, one of the principal Dalmatian Slavophile intellectuals, Dalmatia was part of the 'Slav-Hellenic' peninsula and was populated exclusively by the ' Slav race'; there were no Italians in Dalmatia, and so it was necessary to 'nationalize' the schools, the administration, and the courts in order to erase the traces left by Venetian rule and damage it caused. The Italian culture could survive only within the limits of Slav national character of the country and, in any case, without any recognition as a autochthonus element of Dalmatian society. [3] | ” |

World War I and the related Italian victory, not welcomed by the Slavs, were the events preceding the incidents of Split.

Italians of Split

In the city of Split there was an autochthonous Italian community, which was reorganised in November 1918 through the foundation of the "National Fasces" (not to be confused with Fascism) led by Leonardo Pezzoli, Antonio Tacconi, Edoardo Pervan and Stefano Selem. They arose from the ashes of the Autonomist Party, dissolved by the Austrian authorities in 1915.

There were 2,082 Italians in Spilt according to the 1910 Austrian Census and they were 9.73% of the total population,[4] but they had the best economic status in Split society.

This census data had understated the number of Italians in the city area and this mistake seems to be confirmed by a series of subsequent events. Indeed following the Treaty of Rapallo (1920), the Italians of Dalmatia could opt for the acquisition of Italian citizenship instead of that of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia & Slovenia (later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929). While maintaining residence, despite a violent campaign of intimidation on the part of Yugoslavia, over 900 families of Italian speaking "Spalatini" had exercised the option to be Italians.[5] Furthermore, in 1927 a census was carried out of Italians living outside Italy. In Split and the surrounding area there were counted 3,337 Dalmatian Italians.[6]

So, given that about 1,000 Italians (with their families) left the city following its incorporation into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and estimating a certain percentage of Italians who accepted the "forced" Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes citizenship, it is really possible that 7,000 Italians in the Split area, as said by Antonio Tacconi obtained membership in Italian associations of Split in 1918/1919. This number is more than 3 times that registered in the data from the 1910 Austrian Census.

History

After the Austrian defeat, in the first half of November 1918, Italian troops occupied the Dalmatian territories assigned to Italy by the 1915 London Pact.[7] Split was not one of those areas, but the Italians sent some ships and occupied the city as agreed with the Allies.

The Slav nationalists, who controlled the city with their "National Guard", soon showed huge hostility toward the Italian troops, fearing they could remain forever in the city. Even the arrival of Slav refugees from the London Pact Italian-occupied areas increased the tension. Those refugees were responsible for most of the incidents in the next 2 years.[8]

On November 9, 1918 two French destroyers entered the port of Split. The Italians, mostly concentrated within the old Split city, exposed on the windows of their homes the Italian Flag-Italian tricolour and went to the harbour to celebrate the Triple Entente. But the reaction of the National Guard (Slavs) was immediate. They entered by force the apartments, tore down the flags, beat some of those present and damaged the furniture. Meanwhile, the Austrian commander of a ship already docked at the port (and now with the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes flag) ordered with the megaphone to remove the flags, threatening to open fire.[9]

This was the first of a long series of incidents, which also saw the creation of a classic pattern of propaganda that would be found very often in the next months: the Croatian newspapers – and especially the most extreme of them, Novo Doba,[10] denounced the "Italian provocation". The Italians, however created a complaint report and forwarded it to the Allies.[11] In the following days the municipal authorities of Split were forced to submit a formal apology for the incident.

Other incidents and demonstrations against Italy and the Dalmatian Italians occurred in other cities, like Trogir (Trau) and Kastel (Castelli). The worst took place on December 23 when groups of fanatical Slavs destroyed the offices of the main Italian institutions in Split (the "Fascio Nazionale", the "Gabinetto di Lettura" and the "Società Operaia") and hit many dozens of Italians on the streets, while destroying a lot of Italian-owned shops. The same happened on January 6, 1919 in Trogir.[12]

Italian Admiral Enrico Millo, who was just promoted to Governor of Dalmatia for the area occupied by Italy, quickly sent ships to defend the Italians of Split: on January 12 arrived in the destroyer "Puglia" in the port of the city, amongst huge protests from the Slav community.[13]

On February 24, while an "Allies Commission for the Adriatic" was visiting Split, a huge group of Slavs, in order to show that they were the majority in Split and that they rejected the Italians, attacked the Italian sailors of the "Puglia". Captain Giulio Menini was hit together with some Italians walking on the nearby streets, and again damaged some shops owned by the Italian community.[14] The new Slav authorities were forced to produce another apology and until summer there were only minor incidents.

On September 12 Gabriele D'Annunzio occupied Rijeka (Fiume) and later went even to Zadar (Zara). As a consequence the Italian count Fanfogna organized a similar occupation in Trogir [15] and the Slavs of Split feared something similar was going to happen in their city. Tensions arose and other incidents against the Italians happened in Split in November. The "Caffe Nani" was destroyed and many Italian owned shops were damaged.[16]

The murder of Captain Tommaso Gulli in Split

Until the beginning of 1920 the Italians of Spalato never undertook an attack on the Slavs. They were harassed by Croatian nationalists continuously (as has happened since the end of the XIX century in all Dalmatia.)[17]

After the attack of January 27, 1920 in which nearly all the Italian-owned shops and the offices of Italian institutions were damaged, some Italian sailors of the "Puglia" now under the command of captain Tommaso Gulli, started to defend themselves.

On July 27 another attack against the Italians of Spalato was undertaken and a group of officials of the "Puglia" found refuge in a place near the docks. Captain Gulli ordered a boat to rescue them, but it was blocked by some Slavs and was forced to fire "alarm shots" in the sky to get help.[18]

Soon Gulli went to the rescue with a MAS (boat), but approaching the docks found a huge crowd of nationalist Slavs. Shots were fired at the Italians and for the first time they returned fire.

Another shot hit captain Gulli, while the Italians killed a man on the docks, whose name was Matej Mis. Many versions about what happened were presented in the next days, by the Slavs and by the Italians. Captain Gulli was helped to a Hospital but died the next day, while sailor Rossi survived only a few hours.[19]

In the Kingdom of Italy the reaction to what happened in Split was of rage and indignation. In Trieste fascists and nationalists attacked the Hotel Balkan (called in Slovenian language "Narodni dom" and centre of the Slav activities in Trieste) the next day.

In the following years the Italians of Spalato – under the new regime rule (Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes) were continuously harassed in their institutions, schools and shops and business. Their numbers declined in a slow but steady way.[20]

Allies Commission for the Adriatic

- US admiral Albert P. Niblack

- British admiral Edward Burton Kiddle

- French admiral Jean-Etienne-Charles-Marcel Ratyè

- Italian admiral Umberto Cagni

Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Split Riots:

| “ | Serious anti-Italian disorders occurred on July 11 at Spalato, where the Croat mob murdered the commander of the cruiser "Puglie" and wounded several officers and men [21] | ” |

Notes

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"Split, Croatia, 2011. Mon. 03 Oct. 2011". 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-03. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ A.Bajamonti, Discorso inaugurale della Società Politica dalmata, Spalato 1886

- ^ The Italians of Dalmatia: From Italian Unification to World War I by Luciano Monzali (p65)

- ^ G.Perselli, I censimenti della popolazione dell'Istria, con Fiume e Trieste, e di alcune città della Dalmazia tra il 1850 e il 1936, Unione Italiana Fiume-Università Popolare di Trieste, Trieste-Rovigno 1993.

- ^ Luciano Monzali.Antonio Tacconi e la comunità italiana di Spalato p. 165

- ^ Luciano Monzali. Antonio Tacconi e la comunità italiana di Spalato p.167

- ^ L. Monzali, Italiani di Dalmazia. 1914–1924(section: Un difficile dopoguerra. L'occupazione italiana della Dalmazia settentrionale) p. 50

- ^ G. Menini, Passione adriatica. Ricordi di Dalmazia 1918–1920

- ^ The whole episode is described in L. Monzali,Antonio Tacconi e la comunita italiana di Spalato p. 110

- ^ Novo Doba. Split in the interwar period of Z. Jelaska.(the oblique Vrste nasilja u Splitu svjetska između dva rata in Istriae Acta, 10, 2002) p.391

- ^ L. Monzali,Italians of Dalmatia p.69

- ^ Luciano Monzali. Antonio Tacconi e la comunita italiana di Spalato. p. 113-114

- ^ Silvio Salza. La marina italiana nella grande guerra p.808

- ^ G.Menini, Passione adriatica. Ricordi di Dalmazia 1918–1920 p.82-83

- ^ New York Times: Count Fanfogna "Dictator" of Trau

- ^ G.Menini, Passione adriatica. Ricordi di Dalmazia 1918–1920 p.187-188

- ^ Attacks on Dalmatian Italians before WWI (in Italian)

- ^ G.Menini, Passione adriatica. p.207

- ^ L.Monzali, Antonio Tacconi e la comunità italiana di Spalato p.208

- ^ Read Il lento declino. Gli italiani di Spalato 1922–1935 in L.Monzali, Antonio Tacconi e la comunità italiana di Spalato p. 235

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica by Walter Yust

Bibliography

- Dalbello M.C.; Razza antonello. Per una storia delle comunità italiane della Dalmazia. Fondazione Culturale Maria ed Eugenio Dario Rustia Traine. Trieste, 2004.

- Lederer, Ivo. La Jugoslavia dalla conferenza di pace al trattato di Rapallo 1919–1920. Il Saggiatore. Milano, 1964.

- Menini, Giulio. Passione adriatica. Ricordi di Dalmazia 1918–1920. Zanichelli. Bologna, 1925.

- Monzali, Luciano. Antonio Tacconi e la comunità italiana di Spalato. Editore Scuola Dalmata dei SS. Giorgio e Trifone. Venezia, 2007.

- Monzali, Luciano. Italiani di Dalmazia. 1914–1924 Le Lettere Firenze, 2007.

- Salza, Silvio. La marina italiana nella grande guerra (Vol. VIII). Vallecchi. Firenze, 1942.

- Tacconi, Ildebrando. La grande esclusa: Spalato cinquanta anni fa (in "Per la Dalmazia con amore e con angoscia"). Editore Del Bianco, Udine, 1994

See also

External links

- Gli incidenti di Spalato 1, in Prassi italiana di diritto internazionale, 1426/3 (in Italian)

- L'incidente di Spalato 2, in Prassi italiana di diritto internazionale, 1416/3 (in Italian)

- L'incidente di Spalato e reazione a Trieste, in Prassi italiana di diritto internazionale, 1356/3 (in Italian)

- Italian Navy: Torpediniera "Puglia"

- www.split.info

"[Country_Code" contains a listed "[" character as part of the property label and has therefore been classified as invalid. "[Country_Code" contains a listed "[" character as part of the property label and has therefore been classified as invalid. Dalmatia Split Italians Dalmatia Dalmatian Italians Dalmatia Italy incidents at Spalato Captain Tommaso Gulli Admiral Enrico Millo Admiral Albert P. Niblack