Difference between revisions of "Asparagus"

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | Asparagus has been used from early times as a vegetable and medicine, owing to its delicate flavour and [[diuretic]] properties. There is a [[recipe]] for cooking asparagus in the oldest surviving book of recipes, [[Apicius]]’s third century AD ''[[De re coquinaria]],'' Book III. It was cultivated by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, who ate it fresh when in season and dried the vegetable for use in winter. | + | Asparagus has been used from early times as a vegetable and medicine, owing to its delicate flavour and [[diuretic]] properties. There is a [[recipe]] for cooking asparagus in the oldest surviving book of recipes, [[Apicius]]’s third century AD ''[[De re coquinaria]],'' Book III. It was cultivated by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, who ate it fresh when in season and dried the vegetable for use in winter. It lost its popularity in the Middle Ages but returned to favour in the seventeenth century.<ref name="OBFP">{{cite book | last =Vaughan | first =J.G. | authorlink = | coauthors = Geissler, C.A. | title =The New Oxford Book of Food Plants | publisher = Oxford University Press | year= 1997}}</ref> |

==Uses== | ==Uses== | ||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

White asparagus, known as [[spargel]], is cultivated by denying the plants light and increasing the amount of ultraviolet light the plants are exposed to while they are being grown. Less bitter than the green variety, it is very popular in the [[Netherlands]], [[France]], [[Belgium]] and [[Germany]] where 57,000 tonnes (61% of consumer demands) are produced annually.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.germanfoods.org/consumer/documents/WhiteAsparagusPressRelease.doc | publisher=German Agricultural Marketing Board | title=Asparagus: The King of Vegetables | author=Molly Spence | accessdate=2007-02-26|format=DOC}}</ref> | White asparagus, known as [[spargel]], is cultivated by denying the plants light and increasing the amount of ultraviolet light the plants are exposed to while they are being grown. Less bitter than the green variety, it is very popular in the [[Netherlands]], [[France]], [[Belgium]] and [[Germany]] where 57,000 tonnes (61% of consumer demands) are produced annually.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.germanfoods.org/consumer/documents/WhiteAsparagusPressRelease.doc | publisher=German Agricultural Marketing Board | title=Asparagus: The King of Vegetables | author=Molly Spence | accessdate=2007-02-26|format=DOC}}</ref> | ||

| − | Purple asparagus differs from its green and white counterparts, having high sugar and low [[fibre]] levels. Purple asparagus was originally developed in [[Italy]] and commercialised under the variety name ''Violetto d'Albenga''. Since then, breeding work has continued in countries such as the United States and New Zealand. | + | Purple asparagus differs from its green and white counterparts, having high sugar and low [[fibre]] levels. Purple asparagus was originally developed in [[Italy]] and commercialised under the variety name ''Violetto d'Albenga''. Since then, breeding work has continued in countries such as the United States and New Zealand. |

In northwestern Europe, the season for asparagus production is short, traditionally beginning on April 23 and ending on [[Midsummer|Midsummer Day]].<ref>[http://www.oxfordtimes.co.uk/leisure/4329516.Time_to_glory_in_asparagus_again/ ''Oxford Times'': "Time to glory in asparagus again".]</ref> | In northwestern Europe, the season for asparagus production is short, traditionally beginning on April 23 and ending on [[Midsummer|Midsummer Day]].<ref>[http://www.oxfordtimes.co.uk/leisure/4329516.Time_to_glory_in_asparagus_again/ ''Oxford Times'': "Time to glory in asparagus again".]</ref> | ||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

The English word "asparagus" derives from classical [[Latin language|Latin]], but the plant was once known in English as ''sperage'', from the [[Medieval Latin]] ''sparagus''. This term itself derives from the [[Greek language|Greek]] ''aspharagos'' or ''asparagos'', and the Greek term originates from the [[Persian language|Persian]] ''asparag'', meaning "sprout" or "shoot". | The English word "asparagus" derives from classical [[Latin language|Latin]], but the plant was once known in English as ''sperage'', from the [[Medieval Latin]] ''sparagus''. This term itself derives from the [[Greek language|Greek]] ''aspharagos'' or ''asparagos'', and the Greek term originates from the [[Persian language|Persian]] ''asparag'', meaning "sprout" or "shoot". | ||

[[Image:SkFernlikePlant.jpg|thumb|left|Mature native Asparagus with seed pods in [[Saskatchewan]], [[Canada]] ]] | [[Image:SkFernlikePlant.jpg|thumb|left|Mature native Asparagus with seed pods in [[Saskatchewan]], [[Canada]] ]] | ||

| − | Asparagus was also corrupted in some places to "sparrow grass"; indeed, the [[Oxford English Dictionary]] quotes [[John Walker (naturalist)|John Walker]] as having written in 1791 that "''Sparrow-grass'' is so general that ''asparagus'' has an air of stiffness and pedantry". In [[Gloucestershire]] and [[Worcestershire]] it is also known simply as "grass". Another known [[Colloquialism|colloquial]] variation of the term, most common in parts of Texas, is "aspar grass" or "asper grass". In the Midwest United States and [[Appalachia]], "spar grass" is a common [[colloquialism]]. Asparagus is commonly known in fruit retail circles as "Sparrows Guts", etymologically distinct from the old term "sparrow grass", thus showing convergent language evolution. | + | Asparagus was also corrupted in some places to "sparrow grass"; indeed, the [[Oxford English Dictionary]] quotes [[John Walker (naturalist)|John Walker]] as having written in 1791 that "''Sparrow-grass'' is so general that ''asparagus'' has an air of stiffness and pedantry". In [[Gloucestershire]] and [[Worcestershire]] it is also known simply as "grass". Another known [[Colloquialism|colloquial]] variation of the term, most common in parts of Texas, is "aspar grass" or "asper grass". In the Midwest United States and [[Appalachia]], "spar grass" is a common [[colloquialism]]. Asparagus is commonly known in fruit retail circles as "Sparrows Guts", etymologically distinct from the old term "sparrow grass", thus showing convergent language evolution. |

It is known in [[French language|French]] and [[Dutch language|Dutch]] as ''asperge'', in [[Italian language|Italian]] as ''asparago'' (old Italian ''asparagio''), in [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] as ''espargo hortense'', in [[Spanish language|Spanish]] as ''espárrago'', in [[German language|German]] as ''[[Spargel]]'', in [[Hungarian language|Hungarian]] as ''spárga''. | It is known in [[French language|French]] and [[Dutch language|Dutch]] as ''asperge'', in [[Italian language|Italian]] as ''asparago'' (old Italian ''asparagio''), in [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] as ''espargo hortense'', in [[Spanish language|Spanish]] as ''espárrago'', in [[German language|German]] as ''[[Spargel]]'', in [[Hungarian language|Hungarian]] as ''spárga''. | ||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

=== Metabolism === | === Metabolism === | ||

| − | The biological mechanism for the production of these compounds is less clear. | + | The biological mechanism for the production of these compounds is less clear. |

The speed of onset of urine smell has been estimated to occur within 15–30 minutes of ingestion.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.webmd.com/content/article/43/1671_51089 | publisher=WebMD | title=Eau D'Asparagus | author=Somer, E. | date=[[August 14]] [[2000]] | accessdate=2006-08-31}}</ref> | The speed of onset of urine smell has been estimated to occur within 15–30 minutes of ingestion.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.webmd.com/content/article/43/1671_51089 | publisher=WebMD | title=Eau D'Asparagus | author=Somer, E. | date=[[August 14]] [[2000]] | accessdate=2006-08-31}}</ref> | ||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

=== Prevalence of production and identification === | === Prevalence of production and identification === | ||

| − | Observational evidence from the 1950s showed that many people did not know about the phenomenon of asparagus urine. There is debate about whether all (or only some) people produce the smell, and whether all (or only some) people identify the smell. | + | Observational evidence from the 1950s showed that many people did not know about the phenomenon of asparagus urine. There is debate about whether all (or only some) people produce the smell, and whether all (or only some) people identify the smell. |

It was originally thought this was because some of the population digested asparagus differently than others, so that some people excreted odorous urine after eating asparagus, and others did not. However, in the 1980s three studies from France,<ref> {{cite web | url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1379934&blobtype=pdf | journal=Br J. Clin. Pharmac | title=Odorous urine in man after asparagus | author=C. RICHER1, N. DECKER2, J. BELIN3, J. L. IMBS2, J. L. MONTASTRUC3 & J. F. GIUDICELLI |date=May 1989}}</ref> China and Israel published results showing that producing odorous urine from asparagus was a universal human characteristic. The Israeli study found that from their 307 subjects all of those who could smell 'asparagus urine' could detect it in the urine of anyone who had eaten asparagus, even if the person who produced it could not detect it himself.<ref>{{cite journal | url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1379935&blobtype=pdf | journal=Br J. Clin. Pharmac | title=Asparagus and malodorous urine | author=S. C. MITCHELL |date=May 1989}}</ref> Thus, it is now believed that most people produce the odorous compounds after eating asparagus, but only about 22% of the population have the [[autosomal]] genes required to smell them.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/food/story/0,,1576765,00.html | publisher=The Guardian | title=The scientific chef: asparagus pee| date=[[September 23]] [[2005]] | accessdate=2007-04-21}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.discovery.com/area/skinnyon/skinnyon970115/skinny1.html | title=Why Asparagus Makes Your Pee Stink | author=Hannah Holmes | publisher=Discover.com }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal=Br Med J | volume=281 | pages=1676 | year= 1980 | author=Lison M, Blondheim SH, Melmed RN. | title=A polymorphism of the ability to smell urinary metabolites of asparagus | url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=7448566 | pmid=7448566 | doi =10.1136/bmj.281.6256.1676 }}</ref> | It was originally thought this was because some of the population digested asparagus differently than others, so that some people excreted odorous urine after eating asparagus, and others did not. However, in the 1980s three studies from France,<ref> {{cite web | url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1379934&blobtype=pdf | journal=Br J. Clin. Pharmac | title=Odorous urine in man after asparagus | author=C. RICHER1, N. DECKER2, J. BELIN3, J. L. IMBS2, J. L. MONTASTRUC3 & J. F. GIUDICELLI |date=May 1989}}</ref> China and Israel published results showing that producing odorous urine from asparagus was a universal human characteristic. The Israeli study found that from their 307 subjects all of those who could smell 'asparagus urine' could detect it in the urine of anyone who had eaten asparagus, even if the person who produced it could not detect it himself.<ref>{{cite journal | url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1379935&blobtype=pdf | journal=Br J. Clin. Pharmac | title=Asparagus and malodorous urine | author=S. C. MITCHELL |date=May 1989}}</ref> Thus, it is now believed that most people produce the odorous compounds after eating asparagus, but only about 22% of the population have the [[autosomal]] genes required to smell them.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/food/story/0,,1576765,00.html | publisher=The Guardian | title=The scientific chef: asparagus pee| date=[[September 23]] [[2005]] | accessdate=2007-04-21}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.discovery.com/area/skinnyon/skinnyon970115/skinny1.html | title=Why Asparagus Makes Your Pee Stink | author=Hannah Holmes | publisher=Discover.com }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal=Br Med J | volume=281 | pages=1676 | year= 1980 | author=Lison M, Blondheim SH, Melmed RN. | title=A polymorphism of the ability to smell urinary metabolites of asparagus | url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=7448566 | pmid=7448566 | doi =10.1136/bmj.281.6256.1676 }}</ref> | ||

Latest revision as of 21:26, 11 March 2010

Asparagus officinalis is a flowering plant species in the genus Asparagus from which the vegetable known as asparagus is obtained. It is native to most of Europe, northern Africa and western Asia.[1][2][3] It is now also widely cultivated as a vegetable crop.[4]

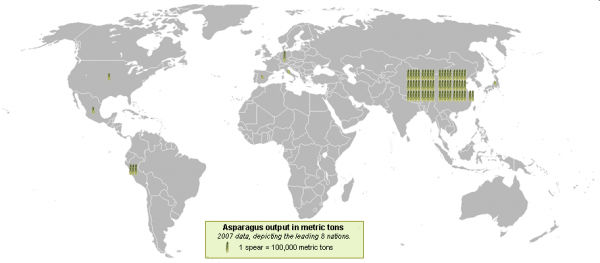

Commercial production

As of 2007, Peru is the world's leading asparagus exporter, followed by China and Mexico.[5] The top asparagus importers (2004) were the United States (92,405 tonnes), followed by the European Union (external trade) (18,565 tonnes), and Japan (17,148 tonnes).[6] The United States' production for 2005 was on Template:Convert and yielded 90,200 tonnes,[7] making it the world's third largest producer, after China (5,906,000 tonnes) and Peru (206,030 tonnes).[8] U.S. production was concentrated in California, Michigan, and Washington.[7] The crop is significant enough in California's Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta region that the city of Stockton holds a festival every year to celebrate it, as does the city of Hart, Michigan, complete with a parade and asparagus queen. The Vale of Evesham in Worcestershire is heralded as the largest producer within Northern Europe, celebrating like Stockton, with a week long festival every year involving auctions of the best crop and locals dressing up as spears of asparagus as part of the British Asparagus Festival.[9]

Biology

Asparagus is a herbaceous perennial plant growing to Template:Convert tall, with stout larissa stems with much-branched feathery foliage. The "leaves" are in fact needle-like cladodes (modified stems) in the axils of scale leaves; they are Template:Convert long and Template:Convert broad, and clustered 4–15 together.Its roots are tuberous .The flowers are bell-shaped, greenish-white to yellowish, Template:Convert long, with six tepals partially fused together at the base; they are produced singly or in clusters of 2-3 in the junctions of the branchlets. It is usually dioecious, with male and female flowers on separate plants, but sometimes hermaphrodite flowers are found. The fruit is a small red berry 6–10 mm diameter.

Plants native to the western coasts of Europe (from northern Spain north to Ireland, Great Britain, and northwest Germany) are treated as Asparagus officinalis subsp. prostratus (Dumort.) Corb., distinguished by its low-growing, often prostrate stems growing to only Template:Convert high, and shorter cladodes Template:Convert long.[1][10] It is treated as a distinct species Asparagus prostratus Dumort by some authors.[11][12]

History

Asparagus has been used from early times as a vegetable and medicine, owing to its delicate flavour and diuretic properties. There is a recipe for cooking asparagus in the oldest surviving book of recipes, Apicius’s third century AD De re coquinaria, Book III. It was cultivated by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, who ate it fresh when in season and dried the vegetable for use in winter. It lost its popularity in the Middle Ages but returned to favour in the seventeenth century.[13]

Uses

Culinary

Only the young shoots of asparagus are eaten.

Asparagus is low in calories, contains no cholesterol, and is very low in sodium. It is a good source of folic acid, potassium, dietary fiber, and rutin. The amino acid asparagine gets its name from asparagus, the asparagus plant being rich in this compound.

The shoots are prepared and served in a number of ways around the world. In Asian-style cooking, asparagus is often stir-fried. Cantonese restaurants in the United States often serve asparagus stir-fried with chicken, shrimp, or beef, also wrapped in bacon. Asparagus may also be quickly grilled over charcoal or hardwood embers. It is also used as an ingredient in some stews and soups. In the French style, it is often boiled or steamed and served with hollandaise sauce, melted butter or olive oil, Parmesan cheese or mayonnaise. It may even be used in a dessert.[14] The best asparagus tends to be early growth (meaning first of the season) and is often simply steamed and served along with melted butter. Tall, narrow asparagus cooking pots allow the shoots to be steamed gently, their tips staying out of the water.

Asparagus can also be pickled and stored for several years. Some brands may label them as "marinated" which means the same thing.

The bottom portion of asparagus often contains sand and dirt and as such thorough cleaning is generally advised in cooking asparagus.

Green asparagus is eaten worldwide, though the availability of imports throughout the year has made it less of a delicacy than it once was.[10] However, in the UK, due to the short growing season and demand for local produce, asparagus commands a premium and the "asparagus season is a highlight of the foodie calendar."[15] In continental northern Europe, there is also a strong seasonal following for local white asparagus, nicknamed "white gold".

Medicinal

Second century physician, Galen, described asparagus as "cleansing and healing."

Nutrition studies have shown that asparagus is a low-calorie source of folate and potassium. Its stalks are high in antioxidants. "Asparagus provides essential nutrients: six spears contain some 135 micrograms (mcg) of folate, almost half the adult RDI (recommended daily intake), 545 mcg of beta carotene, and 20 milligrams of potassium," notes an article which appeared in 'Reader's Digest.' Research suggests folate is key in taming homocysteine, a substance implicated in heart disease.

Folate is also critical for pregnant mothers, since it protects against neural tube defects in babies. Several studies indicate that getting plenty of potassium may reduce the loss of calcium from the body.

Particularly green asparagus is a good source of vitamin C, packing in six times more than those found in citrus fruits.

Vitamin C helps the body produce and maintain collagen. Considered a wonder protein, collagen helps hold together all the cells and tissues of the body.

"Asparagus has long been recognized for its medicinal properties," wrote D. Onstad, author of 'Whole Foods Companion: A Guide for Adventurous Cooks, Curious Shoppers and Lovers of Natural Foods.'

"Asparagus contains substances that act as a diuretic, neutralize ammonia that makes us tired, and protect small blood vessels from rupturing. Its fiber content makes it a laxative too."

Cultivation

Template:See also Since asparagus often originates in maritime habitats, it thrives in soils that are too saline for normal weeds to grow in. Thus a little salt was traditionally used to suppress weeds in beds intended for asparagus; this has the disadvantage that the soil cannot be used for anything else. Some places are better for growing asparagus than others. The fertility of the soil is a large factor. "Crowns" are planted in winter, and the first shoots appear in spring; the first pickings or "thinnings" are known as sprue asparagus. Sprue have thin stems.[16]

White asparagus, known as spargel, is cultivated by denying the plants light and increasing the amount of ultraviolet light the plants are exposed to while they are being grown. Less bitter than the green variety, it is very popular in the Netherlands, France, Belgium and Germany where 57,000 tonnes (61% of consumer demands) are produced annually.[17]

Purple asparagus differs from its green and white counterparts, having high sugar and low fibre levels. Purple asparagus was originally developed in Italy and commercialised under the variety name Violetto d'Albenga. Since then, breeding work has continued in countries such as the United States and New Zealand.

In northwestern Europe, the season for asparagus production is short, traditionally beginning on April 23 and ending on Midsummer Day.[18]

Companion planting

Asparagus is a useful companion plant for tomatoes. The tomato plant repels the asparagus beetle, as do several other common companion plants of tomatoes, meanwhile asparagus may repel some harmful root nematodes that affect tomato plants.[19]

Vernacular names and etymology

Asparagus officinalis is widely known simply as "asparagus", and may be confused with unrelated plant species also known as "asparagus", such as Ornithogalum pyrenaicum known as "Prussian asparagus" for its edible shoots.

The English word "asparagus" derives from classical Latin, but the plant was once known in English as sperage, from the Medieval Latin sparagus. This term itself derives from the Greek aspharagos or asparagos, and the Greek term originates from the Persian asparag, meaning "sprout" or "shoot".

Asparagus was also corrupted in some places to "sparrow grass"; indeed, the Oxford English Dictionary quotes John Walker as having written in 1791 that "Sparrow-grass is so general that asparagus has an air of stiffness and pedantry". In Gloucestershire and Worcestershire it is also known simply as "grass". Another known colloquial variation of the term, most common in parts of Texas, is "aspar grass" or "asper grass". In the Midwest United States and Appalachia, "spar grass" is a common colloquialism. Asparagus is commonly known in fruit retail circles as "Sparrows Guts", etymologically distinct from the old term "sparrow grass", thus showing convergent language evolution.

It is known in French and Dutch as asperge, in Italian as asparago (old Italian asparagio), in Portuguese as espargo hortense, in Spanish as espárrago, in German as Spargel, in Hungarian as spárga.

The Sanskrit name of Asparagus is Shatavari and it has been historically used in India as a part of Ayurvedic medicines.In Kannada, it is known as Ashadhi, Majjigegadde or Sipariberuballi.

Urine

The effect of eating asparagus on the eater's urine has long been observed:

- "asparagus... affects the urine with a foetid smell (especially if cut when they are white) and therefore have been suspected by some physicians as not friendly to the kidneys; when they are older, and begin to ramify, they lose this quality; but then they are not so agreeable"[20]

Marcel Proust claimed that asparagus "...transforms my chamber-pot into a flask of perfume."[21]

Chemistry

Certain compounds in asparagus are metabolized giving urine a distinctive smell due to various sulfur-containing degradation products, including various thiols, thioesters, and ammonia.[22]

The volatile organic compounds responsible for the smell are identified as:[23][24]

- methanethiol,

- dimethyl sulfide,

- dimethyl disulfide,

- bis(methylthio)methane,

- dimethyl sulfoxide, and

- dimethyl sulfone.

Subjectively, the first two are the most pungent, while the last two (sulfur-oxidized) give a sweet aroma. A mixture of these compounds form a "reconstituted asparagus urine" odor.

This was first investigated in 1891 by Marceli Nencki, who attributed the smell to methanethiol.[25]

These compounds originate in the asparagus as asparagusic acid and its derivatives, as these are the only sulfur-containing compounds unique to asparagus. As these are more present in young asparagus, this accords with the observation that the smell is more pronounced after eating young asparagus.

Metabolism

The biological mechanism for the production of these compounds is less clear.

The speed of onset of urine smell has been estimated to occur within 15–30 minutes of ingestion.[26] Research completed and verified by Dr. R. McLellan from the University of Waterloo.

Prevalence of production and identification

Observational evidence from the 1950s showed that many people did not know about the phenomenon of asparagus urine. There is debate about whether all (or only some) people produce the smell, and whether all (or only some) people identify the smell.

It was originally thought this was because some of the population digested asparagus differently than others, so that some people excreted odorous urine after eating asparagus, and others did not. However, in the 1980s three studies from France,[27] China and Israel published results showing that producing odorous urine from asparagus was a universal human characteristic. The Israeli study found that from their 307 subjects all of those who could smell 'asparagus urine' could detect it in the urine of anyone who had eaten asparagus, even if the person who produced it could not detect it himself.[28] Thus, it is now believed that most people produce the odorous compounds after eating asparagus, but only about 22% of the population have the autosomal genes required to smell them.[29][30][31]

References

- ^ a b Flora Europaea: Asparagus officinalis

- ^ Euro+Med Plantbase Project: Asparagus officinalis

- ^ Germplasm Resources Information Network: Asparagus officinalis

- ^ Grubben, G.J.H. & Denton, O.A. (2004) Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 2. Vegetables. PROTA Foundation, Wageningen; Backhuys, Leiden; CTA, Wageningen.

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>United States Department of Agriculture. "World Asparagus Situation & Outlook" (PDF). World Horticultural Trade & U.S. Export Opportunities. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ According to Global Trade Atlas and U.S. Census Bureau statistics

- ^ a b Template:Citation/core

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"Food and Agriculture Organisation Statistics (FAOSTAT)". Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"British Aparagus Festival".

- ^ a b Blamey, M. & Grey-Wilson, C. (1989). Flora of Britain and Northern Europe. ISBN 0-340-40170-2

- ^ Flora of NW Europe: Asparagus prostratus

- ^ Germplasm Resources Information Network: Asparagus prostratus

- ^ Template:Citation/core

- ^ Asparagus Lime Pie Recipe

- ^ British Asparagus

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"BBC - Food - Glossary - 'S'". BBC Online. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>Molly Spence. "Asparagus: The King of Vegetables" (DOC). German Agricultural Marketing Board. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Oxford Times: "Time to glory in asparagus again".

- ^ http://www.ibiblio.org/pfaf/cgi-bin/arr_html?Asparagus+officinalis

- ^ Template:Citation/core

- ^ From the French "[...] changer mon pot de chambre en un vase de parfum," Du côté de chez Swann, Gallimard, 1988.

- ^ Template:Cite journal

- ^ Template:Cite journal

- ^ Food Idiosyncrasies: Beetroot and Asparagus

- ^ Template:Cite journal

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>Somer, E. (August 14 2000). "Eau D'Asparagus". WebMD. Retrieved 2006-08-31. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>C. RICHER1, N. DECKER2, J. BELIN3, J. L. IMBS2, J. L. MONTASTRUC3 & J. F. GIUDICELLI (May 1989). "Odorous urine in man after asparagus". Br J. Clin. Pharmac.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Template:Cite journal

- ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>"The scientific chef: asparagus pee". The Guardian. September 23 2005. Retrieved 2007-04-21. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>Hannah Holmes. "Why Asparagus Makes Your Pee Stink". Discover.com.

- ^ Template:Cite journal

External links

Template:Commonscat Template:Cookbook

- PROTAbase on Asparagus officinalis

- Asparagus officinalis - Plants for a Future database entry

- Template:PDFlink - 2005 USDA report

- Asparagus Production Management and Marketing - commercial growing (OSU bulletin)

- The Stockton Asparagus Festival - held annually every April in Stockton, California

- Growing Asparagus Guide to growing Asparagus

- Asparagus Breeding Program at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey